Innovation and Measuring Progress Division, Directorate for Education

--purple+blog.jpg) |

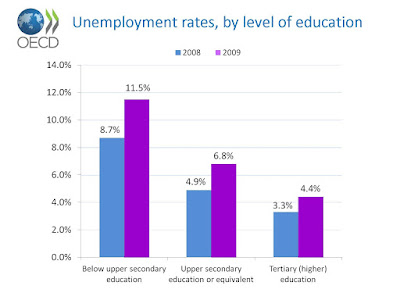

| See instructions below for how to read the chart |

What’s more, existing income inequality may also limit the income prospects of future generations in some countries. In countries with higher income inequality – such as Italy, the United Kingdom, and the United States – a child’s future earnings are likely to be similar to his or her father’s, suggesting that socio-economic background plays a large role in the development of children’s skills and abilities. Meanwhile, in countries with lower income inequality – like Denmark, Finland, and Norway – a child’s future income is not as strongly related to his or her family’s income status. In these countries, the development of children’s skills and abilities has a weaker link with socio-economic factors.

The implications for education policy are clear. Education policies focusing on equity in education may be a particularly useful way for countries to increase earnings mobility between generations and reduce income inequality over time. Countries can work towards this goal by giving equal opportunities to both disadvantaged and advantaged students to achieve strong academic outcomes – laying a pathway for them to continue on to higher levels of education and eventually secure good jobs.

Four top performers on the 2009 PISA reading assessment show the potential of this approach. Canada, Finland, Japan, and Korea all have education systems that put a strong focus on equity – and all have yielded promising results. In each of these countries, relatively few students performed at lower proficiency levels on the PISA reading assessment, and high proportions of students performed better than would be expected, given their socio-economic background.

Yet while each of these countries focuses on equity, they’ve pursued it in different ways. In Japan and Korea, for example, teachers and principals are often reassigned to different schools, fostering more equal distribution of the most capable teachers and school leaders. Finnish schools assign specially-trained teachers to support struggling students who are at risk of dropping out. The teaching profession is a highly selective occupation in Finland, with highly-skilled, well-trained teachers spread throughout the country. In Canada, equal or greater educational resources – such as supplementary classes – are provided to immigrant students, compared to non-immigrant students. This is believed to have boosted immigrant students’ performance.

Income inequality is a challenging issue that demands a wide range of solutions. In a world of growing inequality, focusing on equity in education may be an effective approach to tackle it over the long run.

For more information

On this topic, visit:

Education Indicators in Focus: www.oecd.org/education/indicators

Equity and Quality in Education - Supporting Disadvantaged Students and Schools

On the OECD’s education indicators, visit:

Education at a Glance 2011: OECD Indicators: www.oecd.org/edu/eag2011

Divided we stand: Why inequality keeps rising: www.oecd.org/els/social/inequality

On the OECD’s Indicators of Education Systems (INES) programme, visit:

INES Programme overview brochure

Chart source: Source: D'Addio (2012, forthcoming), “Social Mobility in OECD countries: Evidence and Policy Implications”; OECD (2008), Growing Unequal?, www.oecd.org/els/social/inequality/GU; OECD Income distribution database.

How to read the chart: This chart shows the relationship between earnings mobility between generations of a family, and the prevalence of income inequality in different countries. Overall, countries with higher levels of income inequality tend to have lower earnings mobility between generations, while countries with lower levels of income inequality tend to have higher earnings mobility.